Mercury was a common component of rubberized athletic flooring for two decades, between the 1960’s and 1980’s. It was used as a catalyst with liquid polymers and other components to form a solid rubber-like material that was touted as an excellent replacement for older wood floors.

Thirty years later, many of these floors are nearing the end of their useful life, causing a problem for the schools that own them. Disturbing the rubberized floors causes the material to off-gas mercury as a vapor, posing a health risk to workers, occupants, and the environment. But they can’t be left in place when they begin to degrade.

This was the problem facing both the University of Florida and the University of South Florida prior to their major renovation projects. Here’s how they handled it.

The Facilities

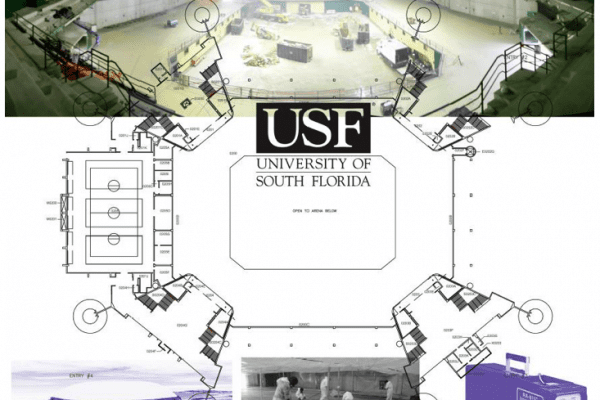

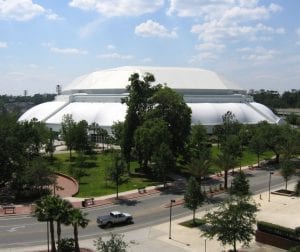

Both the University of Florida (UF) and the University of South Florida (USF) share a common design for their athletic facilities. The O’Connell Center at UF, also known as The O’Dome, was built in 1980 as a 10,000+ seat facility, with a pressurized roof and more than 74,000 square feet of rubberized flooring that contained mercury. The USF SunDome was built the same year using the exact same design.

Both facilities originally used air pressure to keep the dome inflated. When leaks developed, the pressurized dome was replaced with a metal roof. The new roof required supports, which had to be punched through the floors. Failure to put down a vapor barrier caused water to intrude up into the floor, leading to a misshapen floor.

Due to this and other issues common to aging buildings, both universities planned to completely renovate both facilities in 2012 for USF and 2016 for UF. This was to include removing the flooring from both the main floor and a running track on the second floor. The facilities staff at UF had prior knowledge that the flooring could possibly contain mercury, which prompted the USF facilities staff to ask GLE to perform tests of the flooring, which tests confirmed the presence of mercury.

Remediation Design and Consulting

GLE brought in two teams, one for each site, and conducted bulk sampling to determine which materials contained mercury, followed by testing to determine if it was hazardous, according to EPA regulations. Both tests came back positive. We then developed technical specifications for proper removal and disposal of the flooring.

GLE brought in two teams, one for each site, and conducted bulk sampling to determine which materials contained mercury, followed by testing to determine if it was hazardous, according to EPA regulations. Both tests came back positive. We then developed technical specifications for proper removal and disposal of the flooring.

The work was complicated by several factors. There was a very short time frame within which it had to be completed, in order to be ready for the next phase of renovations. Furthermore, while USF was able to close their facility during remediation, UF continued to operate out of the O’Connell Center while some of the work was done. The presence of occupants during remediation required higher levels of protection and careful design for the protection not only of workers but of anyone who entered the building during remediation.

Once the specifications were complete, we assisted both universities in selecting a contractor to complete the work, and then oversaw the remediation.

Remediation

Our specification called for polyethylene tents to isolate the areas while removal was underway. HEPA filters scrubbed the air before exhausting it to the exterior. Anyone who entered the containment area was required to complete 40 hours of training and wear protective equipment including suits, boots, and respirators with mercury cartridges. Signage prevented unauthorized individuals from entering the containment areas.

The work at UF had to be broken down into chunks to accommodate usage schedules, while the work at USF was able to be done continuously. Both facilities had to use chippers to break up the flooring and remove it. We had also found mercury penetration into the concrete, which had to be removed and replaced. Because we helped select contractors with appropriate experience and capabilities, the work was completed without any issues.

Coordination with the Environmental Health and Safety (EH&S) departments at both universities ensured everything was done according to EPA, OSHA, and departmental regulations, including worker safety and hazardous materials disposal. We used a proprietary cloud-based data collection software that allowed GLE to measure mercury levels in real time and enter the data immediately via tablets. At the end of the day, that data was used to generate reports for the remediation teams, EH&S, and other members of the construction team.

We also coordinated with other members of the renovation and construction teams, to ensure that they understood what we were doing and why, and to work around their timelines. This involved numerous meetings prior to beginning the work, as well as weekly meetings throughout the remediation.

Results

University representatives at both facilities were very happy with the remediation work, and it was completed without problems or delay. Altogether, the renovation project at UF cost $64.5 million and included new seating, luxury suites, new locker rooms, a large hanging scoreboard, and much more in addition to the new floors. We are proud to have been a part of both of these successful projects.

Suspect you may have mercury in your athletic flooring? Read this and contact GLE today.